How to MIG weld

MIG has been the most popular welding process for decades, for both professional welders and hobbyists. It’s fast, strong, versatile and fairly easy for most people to learn. Because it’s such a great process, there’s a steady stream of newcomers determined to learn. In this article, we’ll cover the basics — and it will be a good refresher for those who already have experience.

Let’s start with a definition: MIG stands for Metal Inert Gas welding. Typically called Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW), the term MIG welding is much more common, so we’ll use that here.

Setting up your equipment

MIG welding uses a power supply providing constant voltage, most commonly Direct Current Electrode Positive (DCEP). The power supply uses transformers and rectifiers to modulate line voltage, which stabilizes the arc and provides good arc starts — as well as incorporating circuitry to protect against overloading. A work clamp connects the base material to the power supply, completing the circuit. There is a spool of wire, usually housed inside the power supply case, along with a drive mechanism to feed the wire through the cable, toward the gun.

The hand-held gun is the “business end” of a MIG machine. The gun has a trigger that controls several functions simultaneously. Pulling the trigger electrically energizes the welding wire and starts the motor drive, feeding the wire automatically as you weld. MIG welding requires shielding the weld from the atmosphere. To do this, direct shielding gas over the weld area, and control the flow of gas by the trigger on the gun. In other instances, welders might use a flux-cored wire, either alone or with a gas shield.

The majority of MIG welding requries a gas shield — carbon dioxide and argon/CO2 mixes are the most common. The gas bottle has a regulator or flowmeter to set the gas flow. There are many variables here, but a good rule of thumb for light-duty welding is to use about 20 cubic feet per hour of gas flow. Once you’ve developed some skill with the gun, you can experiment with optimizing the amount of gas used.

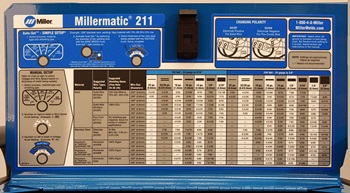

Before making a weld, there are two essential settings to adjust on the welder: the voltage and the wire feed speed. Pro tip: nearly every MIG welder has a chart — including my Millermatic® 211 — often just inside the hinged access cover, which gives you the suggested settings. These are based on the material type and thickness, and the diameter of the filler you’re using. Use these values to adjust the settings on the face of the machine.

Miller pioneered the Advanced Auto-Set™ technology, which allows you to simply set the process, the material thickness and wire diameter, and the machine adjusts the settings automatically. This has worked so well for me that I haven’t read a chart in years!

MIG welding tips

The material needs to be clean to get a good weld; remove any grease or oil before using abrasives. MIG welding is more tolerant of minor surface contaminants than TIG welding, but the cleaner the metal, the fewer problems you’ll have. I often use sanding disks or a non-woven abrasive for cleaning rust, paint or scale off the metal.

Setting up the machine and preparing the material is the easy part. The way you hold and move the gun is the key that governs the quality and appearance of your welds. Whenever possible, it’s best to use a two-handed grip on the gun and to support your hands, wrists, forearms or elbows in a way that allows you to move the gun smoothly, while maintaining precise control. The position of the gun and the distance from the gun to the work are crucial.

The farther you hold the gun from the work, the farther the wire has to extend to meet the metal. The length of the wire between the gun and the base metal is called the stickout. Stickout has a BIG effect on the quality of the weld. Normal stickout is usually around 3/8 inch. Increasing this stickout puts less heat into the metal and can decrease the coverage of the gas shield.

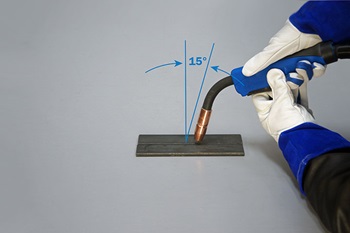

I normally push the puddle when I weld. Since I’m right-handed, that means the motion of the gun is toward my left. In most cases, you should angle the gun slightly in the direction of motion. Called the travel angle, 15 degrees is a good place to start.

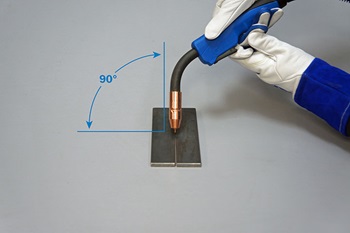

Looking at the gun from the end of a seam, the angle of the gun to the work is called the work angle. For a butt joint, 90 degrees is ideal.

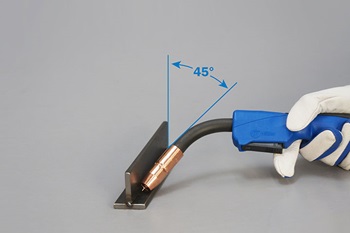

For a 90-degree fillet weld, you’ll normally hold the gun at 45 degrees, although you may need to modify this for thin metals. If a fillet weld is configured as an inverted T (like the photo below), the horizontal portion can dissipate heat on both sides of the weld. The vertical element ends at the weld, so it can’t dissipate as much heat; this sometimes causes burn-through. Angling the gun slightly away from the vertical element will help in situations like this.

The speed you move the gun is very important too. Going too slowly builds up an oversized bead and going too quickly may diminish penetration. Some welders hold the gun steady as they progress, but there are a variety of techniques for weaving or oscillating the gun that may be beneficial. I encourage you to experiment with subtle changes in the way you move the gun, paying close attention to how each change affects the weld. You can learn a lot by talking to and observing other experienced welders.

So how do you judge the quality of a weld? Ideally, the weld bead should be slightly crowned, with the toes or edges of the bead flowing nicely into the base metal. There should be full penetration, but not so much that there is excessive bleed-through on the back of the joint. The width and height of the bead should be fairly consistent, and there should not be any craters or voids. Many people test their practice welds by holding a welded part in a vise and bending the joint until it breaks. Ideally, the metal NEXT to the weld should fracture before the weld bead does.

It takes a lot of practice to get your welds to meet all these criteria. But by following these MIG welding tips and spending time with your helmet down, your welds will only get better!